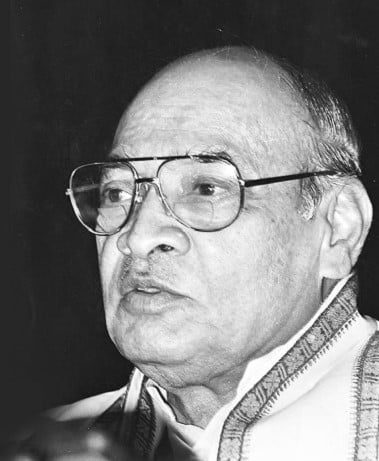

P.V. Narasimha Rao

Prime Minister

P.V. Narasimha Rao was an unlikely candidate to be the tenth Prime Minister of India, having not contested the 1991 elections. To arrest the economic crisis in India, he appointed a competent team of young liberal-minded technocrats and officers, and followed their policy blueprint while removing political roadblocks. As Minister of External Affairs in the Rajiv Gandhi government, Rao had witnessed the balancing act of Deng Xiaoping, paramount leader of China at the time, and the change in China’s fortunes; he aspired to do the same for India. He faced resistance from both the political opposition and elements within his own party, mostly the old guard attached to Nehruvian socialism and unwilling to embrace markets. Resistance also came from certain sections of the Indian bureaucracy, entrenched in socialist institutions, with strong vested interests against markets and privatization. To his party men and to the Left, Rao tactfully pitched the liberalization reforms as grounded in Nehruvian philosophy of self-reliance while simultaneously peppering his speeches with hymns from ancient texts to win over the right-wing nationalists in the opposition. And he maneuvered vested interests by maintaining secrecy and moving reforms swiftly forward. He summed up his economic outlook in 1991 as, “My motto is trade, not aid.”

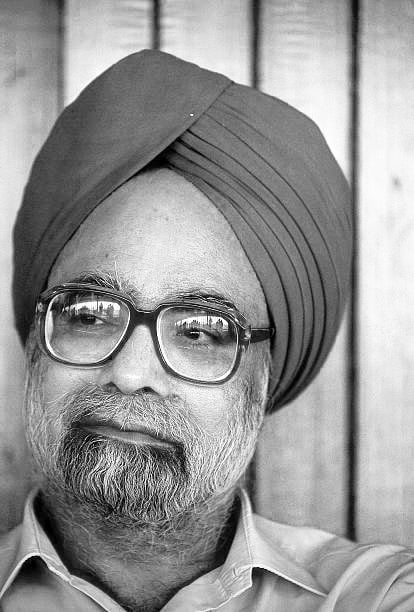

Manmohan Singh

Finance Minister

Though a product of the socialist times, Manmohan Singh’s commitment to reforms can be traced to his mentor I.M.D. Little, a critic of welfare economics and advocate for liberalization in developing economies. In his doctoral thesis supervised by Little, Singh studied trends in Indian exports and argued that openness in foreign trade was essential for growth. He became well acquainted with the particulars of the “East Asian miracle” during his visits to South Korea, Singapore and Thailand. Singh had taught at Panjab University and Delhi School of Economics before serving in key positions: as Chief Economic Adviser to the Government of India, Economic Affairs Secretary in the Ministry of Finance, Governor of the Reserve Bank of India, and Deputy Chairman of the Planning Commission. As Prime Minister Rao’s closest ally, he served as the bridge between the political class and technocrats, and joined the technocrats in creating a cohesive link between the prevailing academic ideas and India’s economic troubles. His big bang reforms set in motion industrial delicensing, decontrolling prices, devaluation, trade liberalization, and financial sector reforms. Singh’s July 24, 1991 budget speech is historic and still serves as a blueprint for the economic reform process in India. Singh continued the reform process, with less success, as India’s thirteenth Prime Minister from 2004 to 2014.

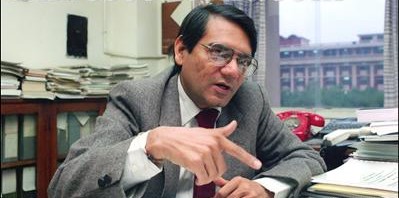

P. Chidambaram

Minister of State for Commerce

Palaniappan Chidambaram, a lawyer from Tamil Nadu and President of the Tamil Nadu Congress Committee, held junior ministerial positions in Rajiv Gandhi’s government. Prime Minister Rao elevated him as Minister of State with independent charge of the Ministry of Commerce. Chidambaram was responsive to the economic situation and on board with the reform strategy. Teaming up with Commerce Secretary Montek Singh Ahluwalia, he announced a slew of trade reforms reducing the use of licenses by the government, accepting foreign partnerships, permitting and incentivizing the private sector to export, and reducing the footprint of the government on import allocations. Initially a committed socialist and trade unionist, Chidambaram’s outlook changed when he took an MBA degree from Harvard Business School. In the United States, he was exposed to an economic system based on free exchange and private enterprise that “appeared to have brought jobs and incomes and prosperity to a much larger proportion of people.” By the 1970s, he became disillusioned in the wake of Indira Gandhi’s bank nationalization, the exploitation of the license permit system which benefitted a few unscrupulous politicians, and the Emergency. Chidambaram continued the reform process as Finance Minister in Manmohan Singh’s government.

Montek Singh Ahluwalia

Commerce Secretary

After his time at Oxford, studying philosophy, politics and economics as a Rhodes scholar, Montek Singh Ahluwalia worked at the World Bank with a group of economists led by Hollis Chenery. This group called for “redistribution with growth,” a view of poverty alleviation that was more congruent with markets. Back in India, within the government in the late 1980s, Ahluwalia started thinking of ideas to resolve the balance-of-payments crisis and also reformulate various sectors of the economy, initially intending to write a blueprint for Rajiv Gandhi in his second term as Prime Minister. After the government changed, Ahluwalia served as an additional secretary to Prime Minister V.P. Singh. Upon the latter’s request Ahluwalia wrote the blueprint for reforms—initially an authorless policy memo dubbed the “M Document.” When V.P. Singh failed to push through any economic reforms and lost his position as Prime Minister, Ahluwalia served as Commerce Secretary in the Chandra Shekhar government, and continued under the Rao administration. When Manmohan Singh devalued the rupee the second time and wanted to follow up with necessary trade reforms, it took only eight hours—from the preliminary briefing Ahluwalia gave Chidambaram, through preparation of the draft reforms and getting final approvals by Rao and Singh—to finalize and announce them.

Amar Nath Verma

Principal Secretary to Prime Minister

As Principal Secretary to Prime Minister Rao, A.N. Verma, a career civil servant, led the PMO, considered the most powerful bureaucratic position within the Indian civil service. Previously as Industry Secretary he was tasked with creating a plan that would serve as a blueprint for the 1991 industrial delicensing reforms. His liberal views were formed during his time in Bangkok at the UN Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific Secretariat, when he witnessed the East Asian transformation through liberalized policies. Verma, with the full backing and clout of the PMO, was the much-needed shepherd who could ensure implementation of the policy reforms during Rao’s tenure. Starting in July 1991, he held weekly meetings where budget details and status of the reforms were discussed. He also oversaw the Foreign Investment Promotion Board placed under the purview of the PMO. He was relentless in ensuring that reforms found traction with different lobbies, especially entrenched Indian firms that feared foreign competition and opposed liberalization.

Naresh Chandra

Cabinet Secretary

Naresh Chandra served as Cabinet Secretary—the senior-most bureaucratic position in India—in the prior V.P. Singh and Chandra Shekhar governments. The political chaos of two governments that lasted less than a year meant all decision-making processes had shifted to Chandra’s desk as Cabinet Secretary, which became the epicenter of managing the balance-of-payments crisis. Rao retained Chandra in his government; Chandra prepared an eight-page memo on the severity of the crisis and the reforms required for the new government’s reference. His brief convinced Rao that instead of ad-hoc solutions of the previous governments, extraordinary and unconventional solutions had to be pursued to find a systematic resolution to the crisis. He oversaw the smooth dismantling of the controls systems for industrial approvals, the Directorate-General of Technical Development, and controllers of various commodities, etc. After his retirement in 1992, he served in Rao’s government as a special adviser to see through the reforms process.

Jairam Ramesh

Officer on Special Duty, Prime Minister’s Office

Before 1991, Jairam Ramesh had worked at the World Bank, been an adviser to the Planning Commission, served as officer on special duty in V.P. Singh’s PMO, and advised the prime ministerial candidate Rajiv Gandhi on the economy. When Rao became Prime Minister, Ramesh was brought on board again. In 1991, Ramesh ensured that the government’s new industrial policy found traction among the Cabinet and the opposition. When the Cabinet initially rejected the proposed reforms, Ramesh added a preamble to the Cabinet Note stating that India’s industrial policy had evolved since Jawaharlal Nehru, both Indira and Rajiv Gandhi had been in favor of this new approach, and that the “government’s policy will be continuity with change.” The Cabinet promptly cleared the policy, without any changes to the reforms it initially opposed. Ramesh’s other notable contributions include his recommendation to A.N. Verma that the Foreign Investment Promotion Board should operate out of the PMO and his suggestion of legislation that would permit limited liability partnerships to enhance the supply of risk capital to the small-scale sector, which was eventually passed in 2008.

Suresh Mathur

Industry Secretary

Suresh Mathur, Industry Secretary, was carried over from the prior Chandra Shekhar government. When appointed to this office, he encouraged and facilitated the work done by Rakesh Mohan’s team on the 1990 Industrial Policy document, refining it and filling gaps. The document and related inputs formed the blueprint for the 1991 industrial reforms announced just before the budget on July 24, 1991.

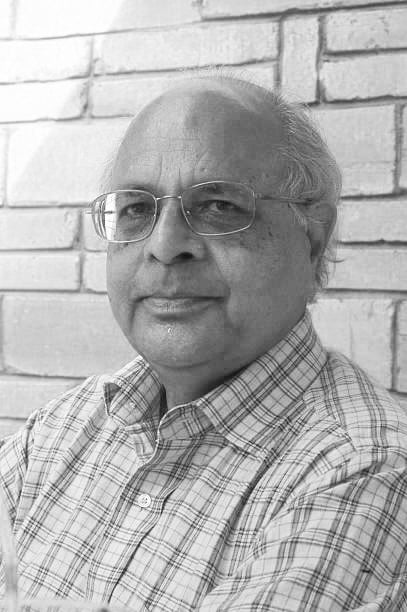

Deepak Nayyar

Chief Economic Adviser

Deepak Nayyar had already served as Chief Economic Adviser to prior governments led by V.P. Singh and Chandra Shekhar before holding the same office in 1991. An academic, Nayyar was one of the first to raise concerns about the impending fiscal and balance-of-payment crises that were brewing, and recommended reaching out to international creditors. Nayyar was instrumental in gaining a US$ 1.8 billion loan from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in January 1991; he also liaised with them during the early months of the Rao administration. He viewed the IMF route as a “tactical withdrawal” that would allow India some time to rebuild its economy. He was not agreeable to the use of the IMF arrangements as a means to push through liberalizing reforms, which possibly explains his departure from service.

Rakesh Mohan

Economic Adviser, Ministry of Industry

Rakesh Mohan joined the Ministry of Industry as an economic adviser in 1988, 3 years prior to the crisis. On Cabinet Secretary T.N. Seshan’s directive, Mohan created the first comprehensive compilation of all industrial licensing policies, control mechanisms, and lists of industries subject to different regulations. His extensive research formed the basis for policy documents that were prepared in the run-up to 1991, including the 1990 Industrial Policy, which he coauthored with A.N. Verma. When the Rao government took charge and industrial policy needed to be reworked within 6 weeks, much of the groundwork had already been completed. Mohan and his team were able to revise proposals quickly to incorporate inputs from ongoing deliberations. After receiving his doctorate in economics at Princeton University, Mohan had begun his career at the World Bank, working on urban development in developing countries. In the 1980s, Mohan was working at the Philippines division at the World Bank when the Philippines faced its worst balance-of-payments crisis and economic recession since its independence and, in response, underwent trade liberalization reforms. His leadership of a large team that designed and prepared a strategy report on industrial policy reforms for the Philippines gave him valuable experience and perspective.

C. Rangarajan

Deputy Governor, Reserve Bank of India, 1982–1991

In 1991, Chakravarti Rangarajan was Deputy Governor of the RBI. His response to Manmohan Singh after Singh called Rangarajan at Prime Minister Rao’s request to hold back the second round of devaluation of the rupee—“But I have already jumped”—is well known. This unshaken commitment to the reform plan characterised the coordination between Rao and Singh’s team and India’s central bank. Within a span of 18 months, Rangarajan oversaw the introduction of export-import (EXIM) scrips (duty credit that can be used as payment of import tariffs) and eventually the adoption of a market-determined exchange rate system. After receiving his doctorate in economics at University of Pennsylvania, Rangarajan taught for several years at IIM-Ahmedabad before joining the RBI. In 1992, he took over as Governor of the RBI and remained in office until 1997.

R. Venkataraman

President of India

Ramaswamy Venkataraman, India’s President in 1991, could be considered the last of the Nehruvian generation. He participated in the freedom struggle, was jailed during the Quit India Movement, and was a member of the Constituent Assembly. A parliamentarian since the birth of the republic, Venkataraman’s experience included stints as Minister for Defense, Home Affairs, and Finance, and as a member of the Planning Commission. As Finance Minister to Indira Gandhi, he had weathered a storm by securing an arrangement with the IMF for five billion special drawing rights from 1981 to 1983. In 1991, Venkataraman was crucial in ensuring political stability, imploring members of the opposition to cooperate with the government until the crisis was averted. He also played a key role in convincing Rao to appoint Manmohan Singh as Finance Minister. His dislike for the devaluation of the rupee in the first month of the Rao administration is well-known; he found merit in other alternatives, like the IMF arrangement he had overseen previously—so much so that he told Singh to not go ahead with the second round of devaluation.

S. Venkitaramanan

Governor, Reserve Bank of India, 1990–1992

In May 1991, the then Prime Minister Chandra Shekhar government used 20 metric tons of confiscated gold to secure a US$ 200 million loan with the Union Bank of Switzerland in order to maintain India’s balance-of-payments. They did this on the advice of S. Venkitaramanan, Governor of the RBI from December 1990 to December 1992. Venkitaramanan tapped into his extensive network and sought help from his counterparts in Japan and the UK. Acting swiftly, he arranged for collateral in the form of physical gold, and had it transported to the UK to raise another US$ 400 million. He also ordered that the RBI come up with a secret crisis management plan to handle a contingency.

S.P. Shukla

Finance Secretary

Surya Pal Shukla continued from the predecessor Chandra Shekhar government as Finance Secretary. Previously Commerce Secretary, Shukla had overseen India’s negotiations under the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade framework. Shukla belonged to the old guard and, along with Deepak Nayyar, objected to some reforms, including the immediate announcement of EXIM scrips. In July 1991 Shukla was succeeded by K.P. Geethakrishnan.

K.P. Geethakrishnan

Revenue Secretary and Finance Secretary

Until S.P. Shukla’s departure, Geethakrishnan was the Revenue Secretary in the Finance Ministry. When he became the Finance Secretary, he was instrumental in devising creative means to meet the IMF’s conditionality of specific fiscal deficit numbers. His approach was dubbed the “Geethakrishnan effect.” On retiring in 1992, Geethakrishnan served as an executive director on the IMF board.

Y.V. Reddy

Joint Secretary, Balance-of-payments Division

In 1991, Yaga Venugopal Reddy was already serving as Joint Secretary, Balance-of-payments Division in the Finance Ministry, where he oversaw India’s balance-of-payments and external debt. Reddy spearheaded the unified exchange rate system to fix the rupee’s value against foreign currencies, in place of the dual exchange rate system. He was instrumental in setting up the External Debt Monitoring Unit which put out credible data on India’s external debt into the public domain. As Member Secretary of the committees on Balance-of-payments (1991) and Disinvestments of Shares and Public Enterprises (1993), he assisted the chairperson, Rangarajan. Previously, Reddy, on leave from bureaucratic work, was an academic exploring various developments in economic theory. He taught at Osmania University, the Administrative Staff College of India, and the London School of Economics. His scholarship during this period covers the relationship between the state and the market, gauging them for their relative strengths and failures, and the role of technology in improving the efficiency of the state and the market.

N.K. Singh

Joint Secretary, Fund Bank Division, Department of Economic Affairs

Nand Kishore Singh, Joint Secretary, Fund Bank Division from 1991 to 1993, negotiated with the World Bank to modulate structural benchmarks and quarterly performance criteria for India. This was followed by tenures as Additional Secretary (Economic Affairs), Expenditure Secretary, and Revenue Secretary working on taxation reforms. In 1994, N.K. Singh was part of a delegation to the India Development Forum in Paris, seeking contracts with multilateral institutions and private investment. An alumnus of the Delhi School of Economics, N.K. Singh was a legacy bureaucrat. His father was the first Secretary of the Planning Commission and later Finance Secretary, which enabled N.K. Singh to witness the socialist years from close quarters. His faith in the markets stemmed from his tenure in the Indian Embassy in Japan. This association also helped secure Japan’s pledge to contribute US$ 300 million in loans to India.

Ashok Desai

Chief Consultant, Ministry of Finance

Ashok Desai was a contemporary of Manmohan Singh and Jagdish Bhagwati at Cambridge, after which he completed his doctoral studies at Cambridge. He succeeded Deepak Nayyar, but the post of Chief Economic Adviser could only be held by someone appointed by the Union Public Service Commission. To circumvent this formality, Desai was designated as chief economic consultant. By the time Desai assumed office in December 1991, much of the balance-of-payments crisis had been averted. He focused on writing longer term policy reports rather than advising on day-to-day matters. He was known for being promarket reformist and had a no-holds-barred communication style, unusual for the environment he was working in.

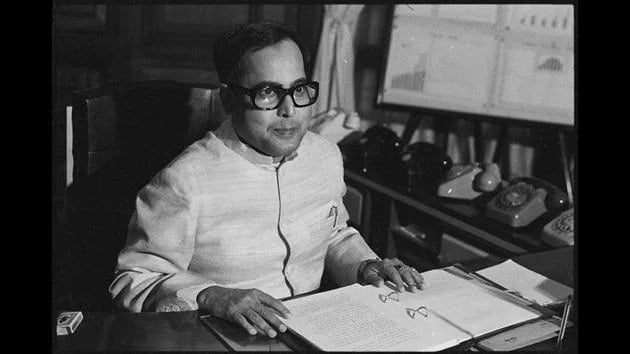

Pranab Mukherjee

Deputy Chairman, Planning Commission

In 1991, Mukherjee was serving as Deputy Chairman of the Planning Commission in the Rao administration. He steered the Commissions’ work on the Eighth Five-Year Plan while factoring the change in circumstances and India’s transition from being a centrally planned economy to a laissez-faire one. He co-created the Gadgil–Mukherjee Formula for resource allocation to the ‘non-special’ category states, which remained in practice until NITI Aayog replaced the Planning Commission. As a long-term colleague and friend of Rao, Pranab assisted him in understanding the nuances of economic issues. Despite his socialist views, he remains the only Finance Minister to have presented budgets in diametrically opposite economic regimes: during Indira Gandhi’s tenure prior to liberalization, and during Manmohan Singh’s term, over a decade after liberalization. In subsequent years, Mukherjee went on to become the thirteenth President of India.

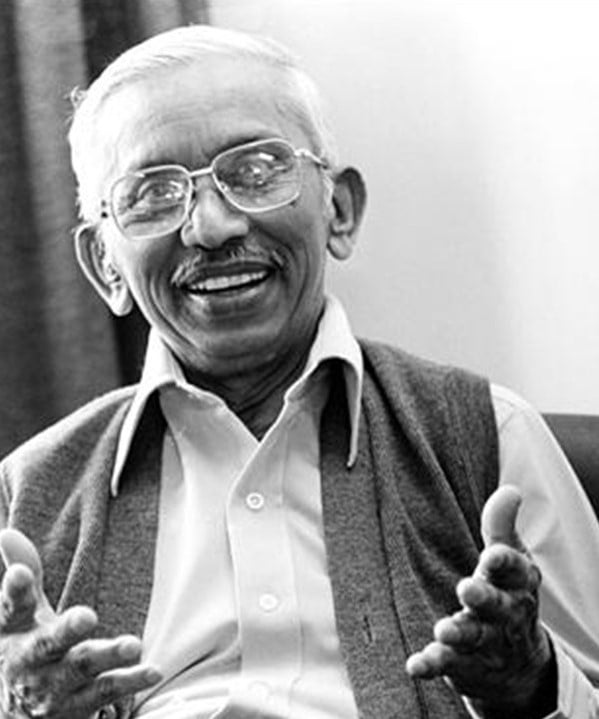

Raja J. Chelliah

Chairman, Tax Reforms Committee

Chelliah chaired the Tax Reforms Committee that was set up in 1991 as part of the reform process. The committee’s report offered recommendations on rationalizing custom duties, abolishing wealth tax on financial assets, and the introduction of VAT at the state level. These recommendations also formed the basis for the budget proposals presented in 1992 and 1993 on direct and indirect taxes. Chelliah was appointed as Fiscal Adviser to Manmohan Singh from 1993 to 1995, to implement the reforms he recommended in the Tax Reforms Committee. Chelliah received his doctoral degree from the University of Pittsburgh. He founded the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy and the Madras School of Economics. He also served as a member of the Planning Commission and the Ninth Finance Commission.

I. Ramamohan Rao

Principal Information Officer

Prime Minister Rao’s Principal Information Officer, Ramamohan Rao had also advised three of Rao’s predecessors. When Rao addressed India for the first time as Prime Minister on the evening of June 22, 1991, his speech was prepared with the combined efforts of Naresh Chandra and Ramamohan Rao. A seasoned propagandist, Ramamohan Rao earlier guided international media coverage of the Indian narrative during the Indo-China War of 1962 and Indo-Pakistan Wars of 1965 and 1967.

P.V.

Narasimha

Rao

Prime Minister

P.V. Narasimha Rao was an unlikely candidate to be the tenth Prime Minister of India, having not contested the 1991 elections. To arrest the economic crisis in India, he appointed a competent team of young liberal-minded technocrats and officers, and followed their policy blueprint while removing political roadblocks.

As Minister of External Affairs in the Rajiv Gandhi government, Rao had witnessed the balancing act of Deng Xiaoping, paramount leader of China at the time, and the change in China’s fortunes; he aspired to do the same for India. He faced resistance from both the political opposition and elements within his own party, mostly the old guard attached to Nehruvian socialism and unwilling to embrace markets. Resistance also came from certain sections of the Indian bureaucracy, entrenched in socialist institutions, with strong vested interests against markets and privatization. To his party men and to the Left, Rao tactfully pitched the liberalization reforms as grounded in Nehruvian philosophy of self-reliance while simultaneously peppering his speeches with hymns from ancient texts to win over the right-wing nationalists in the opposition. And he maneuvered vested interests by maintaining secrecy and moving reforms swiftly forward. He summed up his economic outlook in 1991 as, “My motto is trade, not aid.”

Manmohan

Singh

Finance Minister

Though a product of the socialist times, Manmohan Singh’s commitment to reforms can be traced to his mentor I.M.D. Little, a critic of welfare economics and advocate for liberalization in developing economies. In his doctoral thesis supervised by Little, Singh studied trends in Indian exports and argued that openness in foreign trade was essential for growth. He became well acquainted with the particulars of the “East Asian miracle” during his visits to South Korea, Singapore and Thailand.

Singh had taught at Panjab University and Delhi School of Economics before serving in key positions: as Chief Economic Adviser to the Government of India, Economic Affairs Secretary in the Ministry of Finance, Governor of the Reserve Bank of India, and Deputy Chairman of the Planning Commission.

As Prime Minister Rao’s closest ally, he served as the bridge between the political class and technocrats, and joined the technocrats in creating a cohesive link between the prevailing academic ideas and India’s economic troubles. His big bang reforms set in motion industrial delicensing, decontrolling prices, devaluation, trade liberalization, and financial sector reforms. Singh’s July 24, 1991 budget speech is historic and still serves as a blueprint for the economic reform process in India. Singh continued the reform process, with less success, as India’s thirteenth Prime Minister from 2004 to 2014.

P.

Chidambaram

Minister of State for Commerce

Palaniappan Chidambaram, a lawyer from Tamil Nadu and President of the Tamil Nadu Congress Committee, held junior ministerial positions in Rajiv Gandhi’s government. Prime Minister Rao elevated him as Minister of State with independent charge of the Ministry of Commerce.

Chidambaram was responsive to the economic situation and on board with the reform strategy. Teaming up with Commerce Secretary Montek Singh Ahluwalia, he announced a slew of trade reforms reducing the use of licenses by the government, accepting foreign partnerships, permitting and incentivizing the private sector to export, and reducing the footprint of the government on import allocations.

Initially a committed socialist and trade unionist, Chidambaram’s outlook changed when he took an MBA degree from Harvard Business School. In the United States, he was exposed to an economic system based on free exchange and private enterprise that “appeared to have brought jobs and incomes and prosperity to a much larger proportion of people.” By the 1970s, he became disillusioned in the wake of Indira Gandhi’s bank nationalization, the exploitation of the license permit system which benefitted a few unscrupulous politicians, and the Emergency.

Chidambaram continued the reform process as Finance Minister in Manmohan Singh’s government.

Montek

Singh

Ahluwalia

Commerce Secretary

After his time at Oxford, studying philosophy, politics and economics as a Rhodes scholar, Montek Singh Ahluwalia worked at the World Bank with a group of economists led by Hollis Chenery. This group called for “redistribution with growth,” a view of poverty alleviation that was more congruent with markets.

Back in India, within the government in the late 1980s, Ahluwalia started thinking of ideas to resolve the balance-of-payments crisis and also reformulate various sectors of the economy, initially intending to write a blueprint for Rajiv Gandhi in his second term as Prime Minister. After the government changed, Ahluwalia served as an additional secretary to Prime Minister V.P. Singh. Upon the latter’s request Ahluwalia wrote the blueprint for reforms—initially an authorless policy memo dubbed the “M Document.” When V.P. Singh failed to push through any economic reforms and lost his position as Prime Minister, Ahluwalia served as Commerce Secretary in the Chandra Shekhar government, and continued under the Rao administration.

When Manmohan Singh devalued the rupee the second time and wanted to follow up with necessary trade reforms, it took only eight hours—from the preliminary briefing Ahluwalia gave Chidambaram, through preparation of the draft reforms and getting final approvals by Rao and Singh—to finalize and announce them.

Amar

Nath

Verma

Principal Secretary to Prime Minister

As Principal Secretary to Prime Minister Rao, A.N. Verma, a career civil servant, led the PMO, considered the most powerful bureaucratic position within the Indian civil service. Previously as Industry Secretary he was tasked with creating a plan that would serve as a blueprint for the 1991 industrial delicensing reforms. His liberal views were formed during his time in Bangkok at the UN Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific Secretariat, when he witnessed the East Asian transformation through liberalized policies.

Verma, with the full backing and clout of the PMO, was the much-needed shepherd who could ensure implementation of the policy reforms during Rao’s tenure. Starting in July 1991, he held weekly meetings where budget details and status of the reforms were discussed. He also oversaw the Foreign Investment Promotion Board placed under the purview of the PMO. He was relentless in ensuring that reforms found traction with different lobbies, especially entrenched Indian firms that feared foreign competition and opposed liberalization.

Naresh

Chandra

Cabinet Secretary

Naresh Chandra served as Cabinet Secretary—the senior-most bureaucratic position in India—in the prior V.P. Singh and Chandra Shekhar governments. The political chaos of two governments that lasted less than a year meant all decision-making processes had shifted to Chandra’s desk as Cabinet Secretary, which became the epicenter of managing the balance-of-payments crisis.

Rao retained Chandra in his government; Chandra prepared an eight-page memo on the severity of the crisis and the reforms required for the new government’s reference. His brief convinced Rao that instead of ad-hoc solutions of the previous governments, extraordinary and unconventional solutions had to be pursued to find a systematic resolution to the crisis.

He oversaw the smooth dismantling of the controls systems for industrial approvals, the Directorate-General of Technical Development, and controllers of various commodities, etc. After his retirement in 1992, he served in Rao’s government as a special adviser to see through the reforms process.

Jairam

Ramesh

Officer on Special Duty, Prime Minister’s Office

Before 1991, Jairam Ramesh had worked at the World Bank, been an adviser to the Planning Commission, served as officer on special duty in V.P. Singh’s PMO, and advised the prime ministerial candidate Rajiv Gandhi on the economy. When Rao became Prime Minister, Ramesh was brought on board again.

In 1991, Ramesh ensured that the government’s new industrial policy found traction among the Cabinet and the opposition. When the Cabinet initially rejected the proposed reforms, Ramesh added a preamble to the Cabinet Note stating that India’s industrial policy had evolved since Jawaharlal Nehru, both Indira and Rajiv Gandhi had been in favor of this new approach, and that the “government’s policy will be continuity with change.” The Cabinet promptly cleared the policy, without any changes to the reforms it initially opposed. Ramesh’s other notable contributions include his recommendation to A.N. Verma that the Foreign Investment Promotion Board should operate out of the PMO and his suggestion of legislation that would permit limited liability partnerships to enhance the supply of risk capital to the small-scale sector, which was eventually passed in 2008.

Suresh Mathur

Industry Secretary

Suresh Mathur, Industry Secretary, was carried over from the prior Chandra Shekhar government. When appointed to this office, he encouraged and facilitated the work done by Rakesh Mohan’s team on the 1990 Industrial Policy document, refining it and filling gaps. The document and related inputs formed the blueprint for the 1991 industrial reforms announced just before the budget on July 24, 1991.

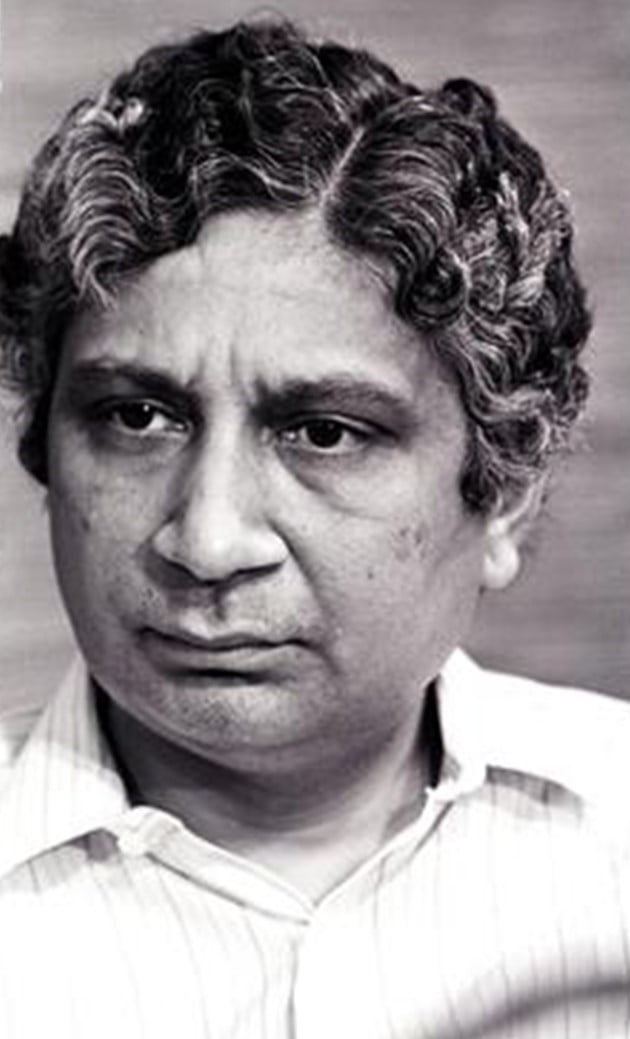

Deepak

Nayyar

Chief Economic Adviser

Deepak Nayyar had already served as Chief Economic Adviser to prior governments led by V.P. Singh and Chandra Shekhar before holding the same office in 1991. An academic, Nayyar was one of the first to raise concerns about the impending fiscal and balance-of-payment crises that were brewing, and recommended reaching out to international creditors.

Nayyar was instrumental in gaining a US$ 1.8 billion loan from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in January 1991; he also liaised with them during the early months of the Rao administration. He viewed the IMF route as a “tactical withdrawal” that would allow India some time to rebuild its economy. He was not agreeable to the use of the IMF arrangements as a means to push through liberalizing reforms, which possibly explains his departure from service.

Rakesh

Mohan

Economic Adviser, Ministry of Industry

Rakesh Mohan joined the Ministry of Industry as an economic adviser in 1988, 3 years prior to the crisis. On Cabinet Secretary T.N. Seshan’s directive, Mohan created the first comprehensive compilation of all industrial licensing policies, control mechanisms, and lists of industries subject to different regulations.

His extensive research formed the basis for policy documents that were prepared in the run-up to 1991, including the 1990 Industrial Policy, which he coauthored with A.N. Verma. When the Rao government took charge and industrial policy needed to be reworked within 6 weeks, much of the groundwork had already been completed. Mohan and his team were able to revise proposals quickly to incorporate inputs from ongoing deliberations.

After receiving his doctorate in economics at Princeton University, Mohan had begun his career at the World Bank, working on urban development in developing countries. In the 1980s, Mohan was working at the Philippines division at the World Bank when the Philippines faced its worst balance-of-payments crisis and economic recession since its independence and, in response, underwent trade liberalization reforms. His leadership of a large team that designed and prepared a strategy report on industrial policy reforms for the Philippines gave him valuable experience and perspective.

C.

Rangarajan

Deputy Governor, Reserve Bank of India, 1982–1991

In 1991, Chakravarti Rangarajan was Deputy Governor of the RBI. His response to Manmohan Singh after Singh called Rangarajan at Prime Minister Rao’s request to hold back the second round of devaluation of the rupee—“But I have already jumped”—is well known. This unshaken commitment to the reform plan characterised the coordination between Rao and Singh’s team and India’s central bank. Within a span of 18 months, Rangarajan oversaw the introduction of export-import (EXIM) scrips (duty credit that can be used as payment of import tariffs) and eventually the adoption of a market-determined exchange rate system.

After receiving his doctorate in economics at University of Pennsylvania, Rangarajan taught for several years at IIM-Ahmedabad before joining the RBI. In 1992, he took over as Governor of the RBI and remained in office until 1997.

R.

Venkataraman

President of India

Ramaswamy Venkataraman, India’s President in 1991, could be considered the last of the Nehruvian generation. He participated in the freedom struggle, was jailed during the Quit India Movement, and was a member of the Constituent Assembly. A parliamentarian since the birth of the republic, Venkataraman’s experience included stints as Minister for Defense, Home Affairs, and Finance, and as a member of the Planning Commission. As Finance Minister to Indira Gandhi, he had weathered a storm by securing an arrangement with the IMF for five billion special drawing rights from 1981 to 1983.

In 1991, Venkataraman was crucial in ensuring political stability, imploring members of the opposition to cooperate with the government until the crisis was averted. He also played a key role in convincing Rao to appoint Manmohan Singh as Finance Minister. His dislike for the devaluation of the rupee in the first month of the Rao administration is well-known; he found merit in other alternatives, like the IMF arrangement he had overseen previously—so much so that he told Singh to not go ahead with the second round of devaluation.

S.

Venkitaramanan

Governor, Reserve Bank of India, 1990–1992

In May 1991, the then Prime Minister Chandra Shekhar government used 20 metric tons of confiscated gold to secure a US$ 200 million loan with the Union Bank of Switzerland in order to maintain India’s balance-of-payments. They did this on the advice of S. Venkitaramanan, Governor of the RBI from December 1990 to December 1992.

Venkitaramanan tapped into his extensive network and sought help from his counterparts in Japan and the UK. Acting swiftly, he arranged for collateral in the form of physical gold, and had it transported to the UK to raise another US$ 400 million. He also ordered that the RBI come up with a secret crisis management plan to handle a contingency.

S.P.

Shukla

Finance Secretary

Surya Pal Shukla continued from the predecessor Chandra Shekhar government as Finance Secretary. Previously Commerce Secretary, Shukla had overseen India’s negotiations under the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade framework.

Shukla belonged to the old guard and, along with Deepak Nayyar, objected to some reforms, including the immediate announcement of EXIM scrips. In July 1991 Shukla was succeeded by K.P. Geethakrishnan.

K.P.

Geethakrishnan

Revenue Secretary and Finance Secretary

Until S.P. Shukla’s departure, Geethakrishnan was the Revenue Secretary in the Finance Ministry. When he became the Finance Secretary, he was instrumental in devising creative means to meet the IMF’s conditionality of specific fiscal deficit numbers. His approach was dubbed the “Geethakrishnan effect.” On retiring in 1992, Geethakrishnan served as an executive director on the IMF board.

Y.V.

Reddy

Joint Secretary, Balance-of-payments Division

In 1991, Yaga Venugopal Reddy was already serving as Joint Secretary, Balance-of-payments Division in the Finance Ministry, where he oversaw India’s balance-of-payments and external debt. Reddy spearheaded the unified exchange rate system to fix the rupee’s value against foreign currencies, in place of the dual exchange rate system. He was instrumental in setting up the External Debt Monitoring Unit which put out credible data on India’s external debt into the public domain. As Member Secretary of the committees on Balance-of-payments (1991) and Disinvestments of Shares and Public Enterprises (1993), he assisted the chairperson, Rangarajan.

Previously, Reddy, on leave from bureaucratic work, was an academic exploring various developments in economic theory. He taught at Osmania University, the Administrative Staff College of India, and the London School of Economics. His scholarship during this period covers the relationship between the state and the market, gauging them for their relative strengths and failures, and the role of technology in improving the efficiency of the state and the market.

N.K.

Singh

Joint Secretary, Fund Bank Division, Department of Economic Affairs

Nand Kishore Singh, Joint Secretary, Fund Bank Division from 1991 to 1993, negotiated with the World Bank to modulate structural benchmarks and quarterly performance criteria for India. This was followed by tenures as Additional Secretary (Economic Affairs), Expenditure Secretary, and Revenue Secretary working on taxation reforms. In 1994, N.K. Singh was part of a delegation to the India Development Forum in Paris, seeking contracts with multilateral institutions and private investment.

An alumnus of the Delhi School of Economics, N.K. Singh was a legacy bureaucrat. His father was the first Secretary of the Planning Commission and later Finance Secretary, which enabled N.K. Singh to witness the socialist years from close quarters. His faith in the markets stemmed from his tenure in the Indian Embassy in Japan. This association also helped secure Japan’s pledge to contribute US$ 300 million in loans to India.

Ashok

Desai

Chief Consultant, Ministry of Finance

Ashok Desai was a contemporary of Manmohan Singh and Jagdish Bhagwati at Cambridge, after which he completed his doctoral studies at Cambridge. He succeeded Deepak Nayyar, but the post of Chief Economic Adviser could only be held by someone appointed by the Union Public Service Commission. To circumvent this formality, Desai was designated as chief economic consultant.

By the time Desai assumed office in December 1991, much of the balance-of-payments crisis had been averted. He focused on writing longer term policy reports rather than advising on day-to-day matters. He was known for being promarket reformist and had a no-holds-barred communication style, unusual for the environment he was working in.

Pranab

Mukherjee

Deputy Chairman, Planning Commission

In 1991, Mukherjee was serving as Deputy Chairman of the Planning Commission in the Rao administration. He steered the Commissions’ work on the Eighth Five-Year Plan while factoring the change in circumstances and India’s transition from being a centrally planned economy to a laissez-faire one. He co-created the Gadgil–Mukherjee Formula for resource allocation to the ‘non-special’ category states, which remained in practice until NITI Aayog replaced the Planning Commission.

As a long-term colleague and friend of Rao, Pranab assisted him in understanding the nuances of economic issues. Despite his socialist views, he remains the only Finance Minister to have presented budgets in diametrically opposite economic regimes: during Indira Gandhi’s tenure prior to liberalization, and during Manmohan Singh’s term, over a decade after liberalization.

In subsequent years, Mukherjee went on to become the thirteenth President of India.

Raja J.

Chelliah

Chairman, Tax Reforms Committee

Chelliah chaired the Tax Reforms Committee that was set up in 1991 as part of the reform process. The committee’s report offered recommendations on rationalizing custom duties, abolishing wealth tax on financial assets, and the introduction of VAT at the state level. These recommendations also formed the basis for the budget proposals presented in 1992 and 1993 on direct and indirect taxes. Chelliah was appointed as Fiscal Adviser to Manmohan Singh from 1993 to 1995, to implement the reforms he recommended in the Tax Reforms Committee.

Chelliah received his doctoral degree from the University of Pittsburgh. He founded the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy and the Madras School of Economics. He also served as a member of the Planning Commission and the Ninth Finance Commission.

I.

Ramamohan Rao

Principal Information Officer

Prime Minister Rao’s Principal Information Officer, Ramamohan Rao had also advised three of Rao’s predecessors. When Rao addressed India for the first time as Prime Minister on the evening of June 22, 1991, his speech was prepared with the combined efforts of Naresh Chandra and Ramamohan Rao.

A seasoned propagandist, Ramamohan Rao earlier guided international media coverage of the Indian narrative during the Indo-China War of 1962 and Indo-Pakistan Wars of 1965 and 1967.